RADIATION PHYSICS: The recently developed sensor is the first of its kind and can measure radiation doses at the level of the individual cell in mixed radiation fields (e.g. measuring all type of radiation at the same time). It enables doctors to obtain a complete picture of how much damage each cell has incurred following treatment.

“This technology means that doctors can monitor and control radiation doses to make sure that only cancer cells are destroyed, with only minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissue”, explains physicist and SINTEF researcher Angela Kok. Kok has been leading the work to develop the sensor as part of her day-to-day research looking into microsystems and nanotechnology.

A million cells on a pin head

Until now, quantification of the radiation dose absorbed by an individual cancer cell has been regarded as a very difficult task. Firstly, each cell is very small, and there may be as many as about a million cells in a single cubic millimetre of tissue. For this reason, and to ensure that the resulting data are correct, a sensor designed to measure radiation has to be as small as the cell itself. In other words, there has to be space for a million sensors in a single cubic millimetre of cancer tissue.

The second problem is that the cells themselves “perceive” the radiation dose in an entirely different way to the sensors. This is why, until now, no sensor has been able to quantify the actual degree of damage caused to cells by a radiation dose.

Mimicking human tissue

Facts about semiconductors:

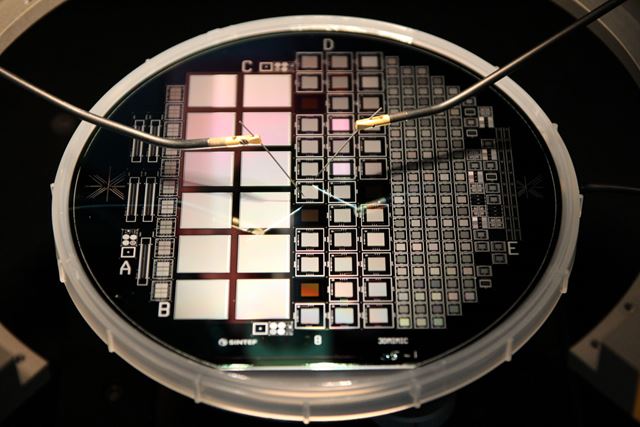

Semiconductor technology is applied in the production of all microchips used in today's electronics industry. Everything from mobile telephones to children's toys and refrigerators contain microchips made according to the same basic principles. The electronics are produced on thin silicon wafers provided with electrical conducting properties using photolithographic processes.

In simple terms, patterns are transferred from a template and deposited onto the silicon wafers using a light-sensitive film. The electronic circuit is built up layer by layer, with each layer having its own distinctive pattern.

As part of these processes, elements such as boron and phosphorous are added to the silicon to provide the chip with the desired electrical properties. Other electrical insulation materials are deposited onto the chip and conductor paths are created using metals such as aluminium, copper or gold.

At SINTEF's microsystems and nanotechnology laboratory, this semiconductor technology is combined with processes designed to manufacture mechanical structures in silicon. This makes it possible to develop sensors that transmit electrical signals when subjected to changes in parameters such as pressure, temperature, acceleration, etc.

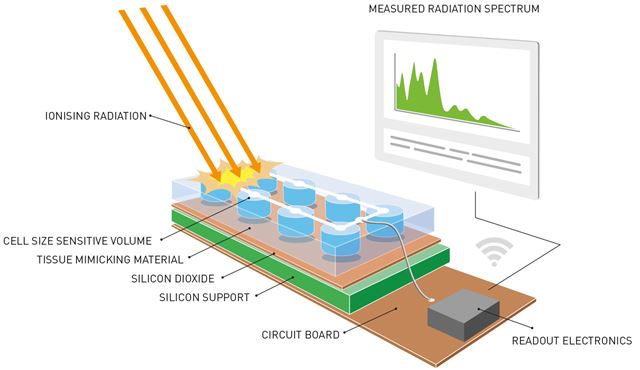

The sensor size issue has been addressed simply by developing a sensor that is as small as a cancer cell. This has been achieved using a technology called semiconductor processing. (Read the fact box.)

The second problem, addressing the different ways in which cells and sensors perceive radiation doses, represented a major challenge. But researchers solved this problem by encapsulating the sensors in a plastic material that mimics human tissue. In this way, the radiation dose measured by the sensors is almost identical to that absorbed by real cancer cells.

This is a sketch of the completed radiology system containing the recently developed sensor. Radiation is absorbed by the sensor, which is the size of a cancer cell, and is then converted into an electrical signal. The signal is then sent to a printed circuit that processes the data and transfers them to a portable device such as a smartphone. The sensor is equipped with an in-built material that mimics human tissue. This ensures that the data are as accurate as possible because the material simulates what happens when the radiation beams encounter the human body.

The sensor, no bigger than a cancer cell, has been fabricated on this silicon wafer using advanced semiconductor processing technology (See the fact box in the article about semiconductor technology). Photo: SINTEF.

The measuring instrument contains microsensors placed alongside each other in a way that creates a “sheet” of sensors mounted on the silicon base. Dispersal across a given area enables the sensors to provide an image of the location within the cell that absorbs the highest levels of radiation.

“In simple terms, we can say that the sensors are used to map variations in radiation intensity absorbed across the exposed cell”, explains Kok.

A result of basic research

The most important component of the new sensor is the element silicon, which is a semiconductor with radiation detection properties.

“When radiation counteracts with silicon the energy is converted into a measurable electrical signal”, explains Kok. “The magnitude of the signal indicates the intensity of the radiation”, she says.

Facts about proton therapy:

Proton therapy is a form of radiation therapy and has become an established treatment in many countries, but not in Norway. Protons are charged nuclear particles that can be used in radiation therapies and have the same impact on cells as mainstream radiation treatments. However, proton beams deliver more tightly focused doses of radiation to tumours than conventional radiation therapies and therefore deliver lower doses to the surrounding healthy tissue. This provides an opportunity to reduce the side-effects caused by radiation treatments. Proton beam therapies also deliver higher doses of radiation to tumour tissue than are possible using traditional radiation treatments.

More than 40,000 patients have been treated using proton therapy worldwide.

Such therapies are used primarily for patients whose tumours cannot be treated with sufficiently high doses using traditional radiation techniques without a significant risk of side-effects, or in situations where current standard radiation doses result in high levels of side-effects. For example, this applies to patients suffering from cancer of the head or throat under circumstances where traditional surgical and/or X-ray radiotherapy fails adequately to control tumour growth, or where control is difficult due to the location of the tumour close to what are normally regarded as critical anatomical structures.

Knowledge Centre for Proton Therapy: http://www.kunnskapssenteret.no/en/frontpage

The very first sensor prototype saw the light of day at SINTEF’s microsystems and nanotechnology lab following a major multinational project involving researchers in the field of medical radiation physics. It was tested recently at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF*) in Grenoble with outstanding results. It has also been tested by Australian researchers at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation.

“This project is a little unusual because our research has resulted in new and fundamental knowledge about what happens in a volume of silicon that has the same dimensions as a typical cell”, says Senior Research Scientist Kari Schjølberg-Henriksen, who has been working with quality assurance on this project. “We’ve taken this knowledge further and have seen it applied in practice after only four years”, she says.

Advancing proton therapy

Research scientist Marco Povoli has been working on this project both as a SINTEF employee and as part of his post-doctoral studies at the University of Oslo. He believes that this innovation may be good news for the future development of cancer treatments using proton therapy. (Read the fact box)

“It appears that proton therapy produces better outcomes for some types of cancer than traditional radiotherapies”, he says. “This is why the University of Wollongong, with which we collaborate, has been working for some time to develop sensors designed for use in proton therapy.

There currently exist no sensors (microdosimetry tools, Ed. note) capable of measuring radiation of this kind, but we realised that our technology could be adapted to develop sensors with the right specifications”, says Povoli.

The team based their work on a technology originally applied to develop sensors for tracking nuclear particles as part of experiments using the particle accelerator at CERN. The technology was used to make the silicon structures that now mimic the effects of radiation on human tissue.

“The fabrication process required more development to optimise the reliability of the results, but we overcame this challenge within a few months”, says Povoli.

The sensor has now been tested with excellent results. According to the research team, it is capable of measuring the true values of radiation doses absorbed by tissue, and with a better spatial resolution than existing equipment. The team is now hoping to be able to contribute towards the future development of radiation therapies for cancer. This can be achieved by providing a more precise quantification of the radiation doses absorbed by cancer tissue, while at the same time reducing the damage incurred by healthy tissue.

The work has been carried out in collaboration with what Povoli describes as world-leading centres in the field of medical radiation physics, including the CMRP (Centre for Medical Radiation Physics) at the University of Wollongong in Australia, the University of Manchester in England, and the ESRF laboratory in Grenoble in France. The ESRF centre specialises in radiation physics.

The project is called “Si-3DMiMic” and is funded by the Research Council of Norway as part of its NANO2021 programme.

The sensor that has formed the starting point for the project has been patented by the CMRP under U.S. Patent No. 8421022 B2.