The largest wind turbines currently operating in the North Sea have an output of around six megawatts. The turbines of the future will be far bigger.

"We are looking into wind turbine structures capable of output of the order of 10 megawatts. Their overall structure will be about 200 metres in height and the actual rotor blades will have a diameter of 180 metres. The stresses on a structure of this scale are enormous," says Petter Andreas Berthelsen, Research Manager at SINTEF Ocean.

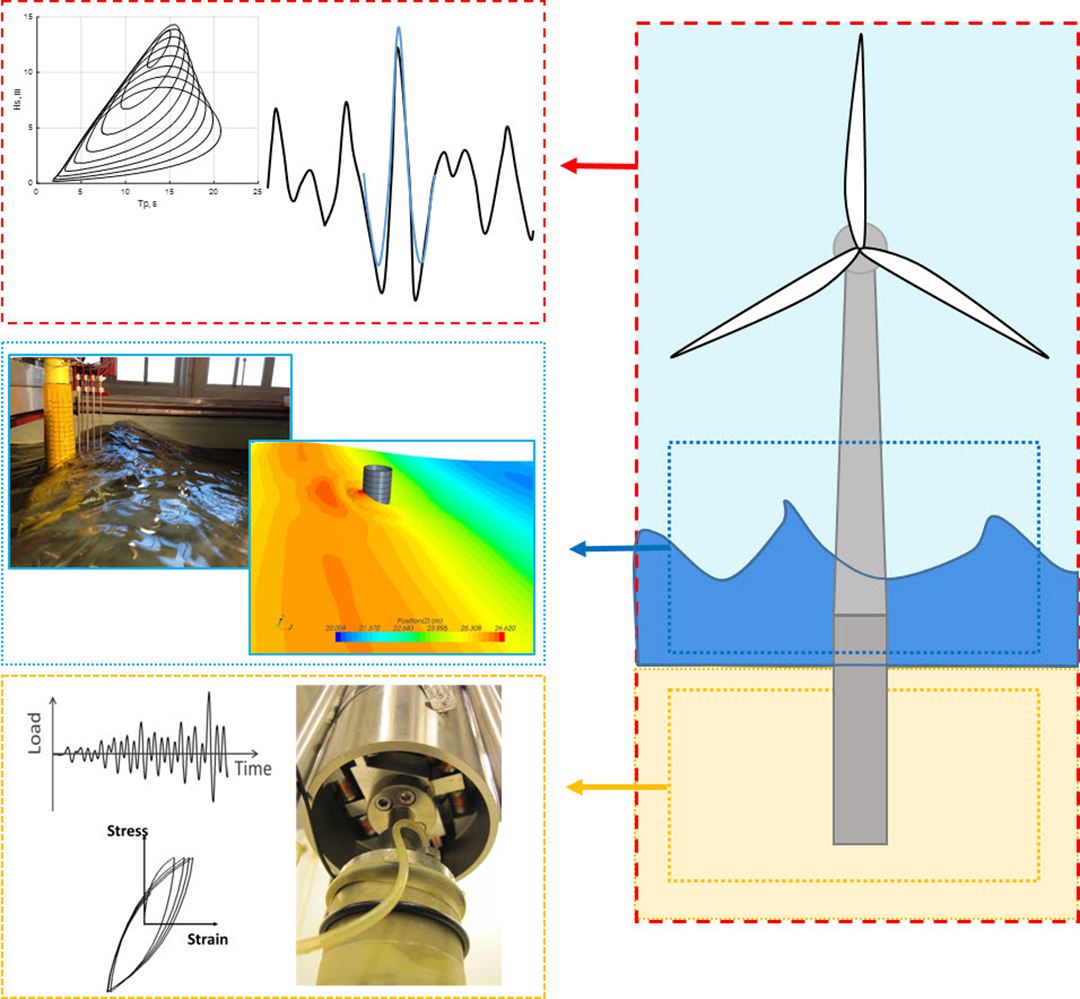

Building these innovative wind turbines demands additional knowledge of how the structures react to wind and waves, as well as how they affect the ground around their foundations. Research scientists will therefore try to develop more accurate and reliable methods for calculating loads on offshore wind turbines and in particular on the monopile itself. This is the actual column which is attached to the seabed.

"First we will carry out computer simulations of both wave loads and the interaction between the monopile and the seabed. Then we will use model trials to verify our discoveries," says Berthelsen.

"When the structure becomes larger one has to take into account not only how the waves affect the column, but also how the column affects the waves. At the same time there is a complex interaction between the monopile and the seabed," the research scientist explains.

Why are large wind turbines more attractive than smaller ones?

Increasing the size of offshore wind turbines contributes to a reduction in the price of energy supply.

WAS-XL (Wave Loads and Soil Support for Extra Large Monopiles) is a so-called Knowledge-building Project for Industry (KPN), in which 80 per cent of the funding comes from the Research Council of Norway while the remaining 20 per cent is provided by the industry. Norwegian companies such as Statoil, Multiconsult and Green Entrans are involved in the project, along with energy providers in Germany and France, among others. SINTEF, NTNU and NGI are providing research scientists for the WAS-XL project.

"We have extensive knowledge of wind turbines in shallow water, but larger turbines and structures provide new challenges. We want to expand the boundaries, but in so doing we have to be absolutely sure we are getting the design of the wind turbines right. Hence this project is just what we are looking for," says Ole Havmøller, one of Statoil's research scientists.

Statoil is developing and operating offshore wind turbine farms in the UK and Germany and plans to expand these activities in the future.

"The more knowledge we have, the more efficient the wind turbine farms will be. We are looking forward to working on this project in the future," says Havmøller.

Harald Sund of Multiconsult agrees:

"We have done a lot of work on different steel structures for the offshore oil and gas sector. As well as in the field of construction, we have expertise in hydrodynamics and soil mechanics. We also have a lot to learn from the wind turbine researchers," says Sund, a Senior Engineer at the company.

The research project will have a duration of four years and the preliminary results are expected in the first half of 2018.